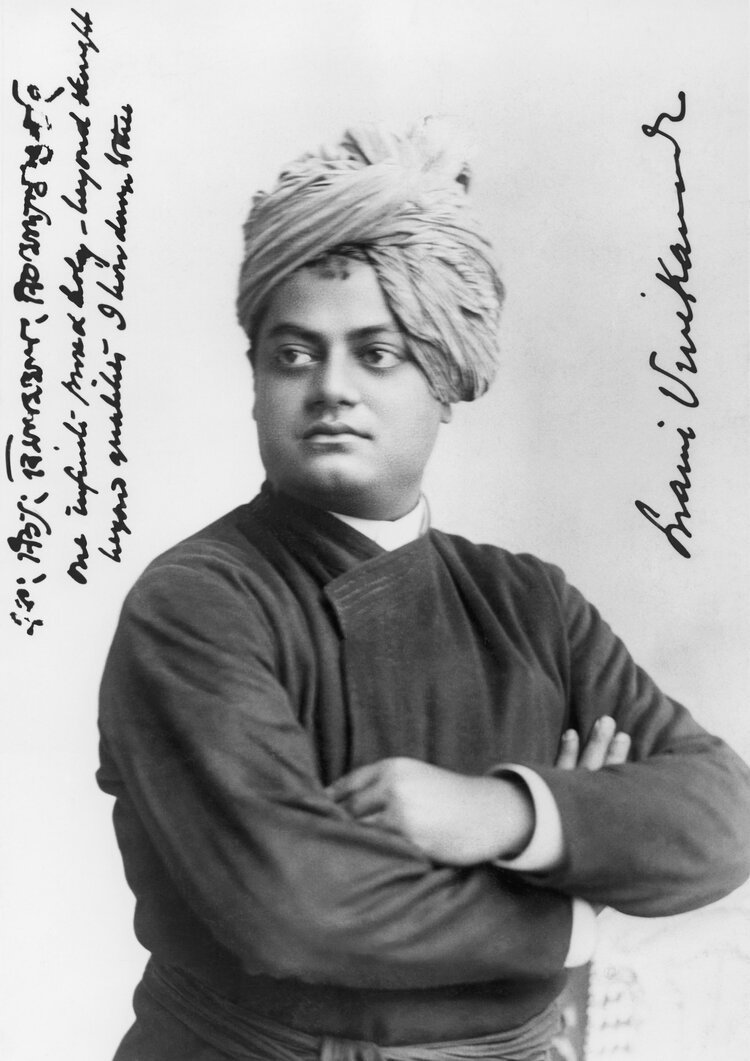

Swami Vivekananda (January 12th ‘1863—July 4th ‘1902) emerges onto Indian history like a golden fire—an Agni beset upon the despair filled forests of late 19th century India. So incandescent was his presence that nearly 120 years after it ceased to burnish the world of religious thought, a careful observer can still glean much from his dimming but luminous halo. Vivekananda’s guru Ramakrishna Paramahamsa described him—even while he was still known as Narendranath Dutta in the days before his ordination as a monk—as being ‘ishwarakoti’ which was a mystic’s way of saying that Vivekananda’s life was blessed by the effulgence of God. But ensconced within the taxonomies of Ramakrishna’s benedictions, this descriptor held other portents too. According to Ramakrishna, Vivekananda was marked by no ordinary blessing but rather, it endowed him with additional responsibilities to help others find salvation from their respective cycles of life and death. In a recent paper, the monk-philosopher Swami Medhananda notes [“Śivajñāne jīver sevā: Reexamining Swami Vivekananda’s Practical Vedānta in the Light of Sri Ramakrishna”, 2019] that in Ramakrishna’s taxonomy of spiritually perfected beings, there are two types: the jnani and the vijnani. Loosely, one can think of these typologies analogically: among those who have seen the true nature of reality, the jnanis are the grammarians and the vijnanis are the poets. The jnani sees the world as a house of illusion and attains his spiritual ends through knowledge when he recognizes that the pluripotent reality of the world is ultimately an expression of a transcendent inertness (nirguna brahman). It is a form of realization of cosmic oneness that ascribes little value for the colors and qualities that birth the hurly burly of our everyday life. In contrast, the vijnani realizes that the world is a house of hilarity, or perhaps even an abode of absurdity. But the vijnani’s psychological understanding of the world is not a comic’s idea of hilarious, a playwright’s sense of the absurd or even the cynic’s view that the world is a poisoned chalice we are condemned to drink out of. But rather a vijnani is marked by his profound recognition that the ultimate truth of the world is both brimming over with qualities and is lacking in the very same. The vijnani, like some quantum particle, exists in various states of the world at the same instance on account of his or her being able to ‘see’ the multidimensional valences of truth. Vivekananda, his guru claimed, was a vijnani and therefore asked him to live up to his potentialities—to experience Brahman and yet belong to this world. In the exhaustive chronicles of Ramakrishna’s lives and lessons, the writer Mahendranath Gupta tells us: “Even before meeting Narendranāth, the Master had seen him in a vision as a sage, immersed in the meditation of the Absolute, who at Sri Ramakrishna's request had agreed to take human birth to assist him in his work.”

What was the role of these expectations in Vivekananda’s understanding of his own life? What does it mean to be cast early on in life as a spiritual exemplar and be entrusted with helping others journey from the gross realities of the here-and-now to the other shore where a recognition of a sublime unity of all Creation awaits. Vivekananda was expected to become “a huge log that not only [could go] across to the other shore but [was also expected by his Guru to] carry many animals and other creatures as well”. What does the charisma of a mystic teacher do to an earnest middle class youth with spiritual aspirations? By asking such questions, these become ways of trying to construct a narrative about a life that was earmarked with soteriological goals early on. In this way of thinking, it is Ramakrishna who is the Master and Vivekananda is, as Gupta describes him, merely “a strong instrument”. But there is another way of thinking about this life story, one that de-centers the previous narrative. It is also perhaps a more Indic way of thinking about pedagogy across generations. In this way of reading, Gurus appear in the lives of a few to awaken them from some primordial sleep to a greater purpose. Viewed thus, Ramakrishna’s exhortations, excoriations, and encouragements were merely the prod to stir a soporific Naren into a wakeful Vivekananda. There is also a third, and arguably more democratic, way of framing their relationship. Per this view, Vivekananda and Ramakrishna rotate on their own life axes but also revolve around each other, like a pair of binary stars—whirling, hurtling, and falling towards other. However one may think of these efforts to frame this life story, the spiritual consecration of a young man as one destined to arise himself and awaken others had consequences on various levels—the personal, the psychosomatic, the psychological, and the philosophical—that any scrupulous biographer of Vivekananda must engage with.

But Vivekananda was also a man, a teacher, a guru, who was born into a particular moment of the late 19th century India. Each of these identities found themselves engaging with different waves of history—some vast and and others intimate—as a result of which telling his life story is more complex than a biography of a conventional late 19th century figure. From deep antiquity there came monster [longue durée?] waves such as the traditions of Vedanta and Tantra worship, in front of which Vivekananda adopted a stance of humility and reverence. Other waves were large too but they were more providential—like the metamorphoses of caste as an institution under colonial modernity and the birth of modern science in India while steadily being part of a global network of knowledge. Faced with these ‘conjunctures’, his attitude was often one of profound skepticism along with a accommodationist view that old institutions could survive in new ways. A few other historical waves that lashed into his life were crises and opportunities—eddies and riptides—born from the personal lives of his interlocutors. When faced with these demands, his behavior is harder to characterize into simple dichotomies of modern or traditional, progressive or conservative—in parts, this is also because it involved him sidestepping debates as and when they no longer mattered to him. The result of an attempt to study this kaleidoscopic persona is that we are forced to often ask ‘which’ Vivekananda are we talking about? Vivekananda the philosopher-theologian, the institution builder, the observer of Indian and Western mores, the itinerant guru, or the interpreter of spiritual malaise. Perhaps these strands of his persona can no more be disentangled than in any other life, but Vivekananda’s case he presaged the kind of questions that founding fathers and mothers of the Indian republic would come to face in the 1947-50 period. He, therefore, had to negotiate with a regressive Indian social order where urgent evolutions were necessary.

[On his experiences of caste in Malabar in modern day Kerala, Vivekananda writes: “Was there ever a sillier thing before in the world than what I saw in Malabar country? The poor Pariah is not allowed to pass through the same street as the high-caste man, but if he changes his name to a hodge-podge English name, it is all right; or to a Mohammedan name, it is all right. What inference would you draw except that these Malabaris are all lunatics, their homes so many lunatic asylums, and that they are to be treated with derision by every race in India until they mend their manners and know better.” - From ‘The Future of India’]

Such instances of extreme social inequities within a social order, in turn, meant discovering hermeneutical strategies that shook up an ancient legacy but nevertheless sought means and discourses rooted in Indic religions to cohere identities into a common socio-political entity. He also discovered that the body politic of his age was one where both Hindu and Muslim identities had begun to congeal into political expressions—with an added perversity that adherents of both religions often borrowed great parts of their own self-descriptions from Orientalist discourses that the British pedagogues taught them. Once British colonialism ended the centuries long complexly motivated Muslim political power in much of North India, more fundamental questions came to the fore including the nature of horizons in political imaginations as well as the aporia that purportedly lay at the heart of Indian society—a rift that may very well have found strength because of the manner in which descriptions were articulated and contextualized. On his own home turf of theological disquisitions, he found his efforts to articulate a Practical Vedanta—a creed of service to Man and sublimation unto God—attacked on two fronts: on one side, the Western philosophers, Indologists, and Christian missionaries sought to steadily efface his innovations (during his life and posthumously) as either a form of syncretism inspired by Schopenhauer or misunderstood it as merely a confirmation of Orientalist cliches in which Hindus could only be metaphysicians and little else. On the other ends, Hindu society—from the orthodoxies to his own brother-disciples—diversely interpreted his works as a drift from traditional ritualism on one side and the dilution of Ramakrishna’s teachings on the other.

[Ruth Harris writes: “Even before his trip to America, he had tussled with his guru-brother Ramakrishnananda, who had set aside a special room at Baranagar to worship Ramakrishna’s relics and his slippers, objects that linked the divine presence to his human incarnation. Ramakrishnananda furiously grabbed Vivekananda by the hair and threw him from the room. The others were astonished by the anger that overtook the ordinarily peaceable Brahmin mathematician. So was Vivekananda; he did not interfere again—but the incident shows the difficulty in converting his fellows to his ideas.”]

Amid these varying pulls of history, society, and theology—the life of Vivekananda the man is often lost to interpretations and innuendos. The actual lived-life, one in which disease and travels, cooking and costumes figure has been effaced. Instead a mythology has taken root. The biography (‘Guru to the World’) by Professor Ruth Harris is an effort to excavate the man buried under a century of readings and misreadings. On the topsoil now, new imaginaries have emerged and newer ideological claims have enlisted him in their respective stories. Harris’ work, in contrast, is an effort to bring out his contradictions and infelicities along with his ability to be a luminous self-born presence in modern Hindu thought as well as one who fashioned his persona on a global stage while still aspiring to return to the ways of a solitary monk. Vivekananda the man who emerges in her work has a joyous sense of humor with a “sometimes cutting, but more often teasing, sense of fun”. But he is also capable of expressing anger (whether he actually felt anger is harder to infer), and actively pursued solitude whenever he could. He was also one who sought to rattle people of their self-indulgent and unthinking prejudices in hopes of bringing them to the middle grounds of any discourse. The irony, of course, is that to do this sustainedly—as a life project in which he was committed to awakening others—meant negotiating an ages old tension which manifests a constant commitment to the ideal of radicalism inherent in the world-negating ways of a Hindu sannyasin while still living in the very same world. But, as the philosopher Arindam Chakrabarti reminds us that Vivekananda also instructed us that ‘mantra (ritual), tantra (esotericism), praan (breathing exercises), niyaman (law), mathamat (religious doctrines), darshan (religious insight), vigyan (sciences), tyaag (renunciation), bhog (hedonism)’ were all ‘budhir vibhram’ (the frenzies of the mind). Only love, love, and love was the true state of being.

* * *

My conversation with Professor Ruth Harris was an effort to help me think about Vivekananda the man as he travelled through history during his brief 39 year old life. In the below conversation, I had a few questions in mind which I had shared with Professor Harris so that she could think about them as well. But, no planned conversation survives contact with the spoken word. I have edited this conversation to remove repetitions, fillers, and pauses—in hopes of making this more readable—while still hopefully retaining the informality with which we spoke. Where particularly relevant, I’ve added some quotes from original texts.

Our conversation was not about Vivekananda the Vedantin or even Vivekananda the Philosopher whose voluminous writings have allowed for interpretative encrustations to recast him—from the Marxist-Leninists to Jawaharlal Nehru and Narendra Modi—in their own political light. Instead this was a conversation about Vivekananda as a life thrown into history. What I particularly liked about Professor Harris’ biography was her underlying sense of generosity towards the man—unlike other more recent efforts which devolve into a gotcha scholasticism with little insight to Vivekananda’s life-journey itself. In one sense, she sees him as no different than most of us, as somebody trying to figure things out things as he goes along; but she also sees in him somebody who was not like us—as one, who despite living in the world of telegraphs and steamers, he belongs to a great lineage of Hindu monks who sought to address the times they lived in, and the ones that are to come, using the vocabulary of their present and past to assert that the world is a manifestation of God, which nevertheless is in great need for human intervention, generosities, and willfulness. He argued that this way—of thought, action, and compassion—was the way of the Upanishads and Dharma itself.

All errors are mine.

* * *

The golden lights of the afternoon sun at Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu ~ from my travels there in 2011.

Keerthik Sasidharan (KS, hereafter):

There is a unique interpretive problem about figures who straddle across temporal thresholds of centuries. Where do they belong? Jonathan Sperber who wrote a biography of Karl Marx with a subtitle, “A Nineteenth Century Life”—writes: “The view of Marx as a contemporary whose ideas are shaping the modern world has run its course and it is time for a new understanding of him as a figure of a past historical epoch, one increasingly distant from our own.” In contrast, when I read and hear Ramachandra Guha write about Gandhi, he suggests and articulates that Gandhi’s message is particularly alive in the 21st century, especially his views on environment and consumerism. Given this kind of conscious efforts by biographers to describe their subjects within or without time frames, how must we think of Swami Vivekananda? Is he a 19th century figure reacting to the first wave of globalization that arguably began in 1850s; is he a 20th century figure who foreshadowed a revivalist strain in Indian consciousness and has run out of relevance; or is a prophetic figure whose speeches and writings will annotate Hindu and religious thought in the decades to come?

Ruth Harris (RH, hereafter):

The book was premised on the idea that it was about Swami Vivekananda being a late-19th century figure and very much a part of his time. I was trying to understand his life not from our present era, but to place him in the world of the 1893 Parliament, of “mind control," healing, and Orientalism, as well as the emergence of American Pragmatism, Christian Science and theosophy. To understand what it meant, both for him and those who heard him. And it took a lot of historical imagination because it's not only Vivekananda whose personae has been overlain with myth and legend for decades. Western women [who were Vivekananda’s friends and acolytes] and people like William James equally had a cliché-ridden vision of the ‘Oriental’ and Indian metaphysician. They were surprised by this man who had read what they had read, and who easily engaged with their concerns, while trying to share his own unaccustomed teachings. I felt that this was my job as a historian, to understand him both in his Indian world and in his global context, while also connecting the two. I also wanted to say what he said, because I find people attribute things to him that he really didn't say.

KS:

You begin your illuminating Lourdes book [‘Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age’] by talking about French doctors in late 1800s who confidently spoke of the imminent end of religion. Around the same time, Vivekananda’s life enters its 20s and 30s inside a coordinate system whose three dimensions were the ancient corpus of Advaita Vedanta, the Kali worshiping tantra ritualism that has spanned centuries, and in contrast to both, the relatively young neo-Hinduism of the Brahmos in Bengal. And then orthogonal to all—a kind of fourth dimension—is the vast and growing body of 19th century science. In a sense, it was inside this four-dimensional space—a tesseract of consciousness, if you will—that his psyche and mind matured. Can you speak to this?

RH:

Many, including many Indians, [today] think about Vivekananda as somebody who almost takes the “magic” out of Hinduism. Without the images and the ceremonies, Hinduism, they might argue, became more like Protestantism. Others oppose this view, and argue that how Vivekananda was so wonderful because he showed that service mattered, that the worshipping of other human beings captured the ‘modern’ essence of Hinduism by placing images and rituals in second place to service. But that’s not at all what Vivekananda said. He always admired Ramakrishna for realizing everything through Kali. Even though he felt that Advaita Vedanta was the height of spiritual accomplishment, he was keen that each person find his or her own path. He constantly reiterated this truth while he was in India and in America and Europe. Because of his belief in the different paths, he found Ramakrishna’s mysticism remarkable—it spanned different Hindu systems of belief and practice but also enabled Ramakrishna to experience Islam and Christianity and to acknowledge that they too were paths to God.

But his universalizing message was also crafted to provoke, to make people think ‘outside the box’. While in America, he railed against Christian exclusivism and argued ‘there’s not just one way, and it's certainly not only through Christ alone’. And he also railed against the hubris of scientific epistemology and the view that it would triumph over spirituality. He wanted to unite science and religion and thought that Ramakrishna was more important than Tyndall [an Irish and scientific polemicist]. He also taught that the Enlightenment legacy—a legacy that many still think of as universal —was not sacrosanct. And that there were other forms of universalism besides Enlightenment rationality.

And Vivekananda is the first person that I encountered from the 1890s to package up those ideas [of critique]. He also recognized that both Christian exclusivism and western science were used to beat Indians: the argument went that Indians were natural metaphysicians, and so they couldn't be scientists; they weren't Christians, so they had to be heathens. His was an important critique of colonialism. [But] it is haphazard and delivered in lectures, but it is also extremely powerful, if not always as systematic as we might want. He believes that science will confirm Advaita and that Science should be a handmaiden to Advaita. And when William James said in the Varieties of Religious Expreience that Hinduism was ultimately nothing more than ‘a sumptuosity of security’

[“Observe how radical the character of the monism here is. Separation is not simply overcome by the One, it is denied to exist. There is no many. We are not parts of the One; It has no parts; and since in a sense we undeniably are, it must be that each of us is the One, indivisibly and totally. An Absolute One, and I that One, — surely we have here a religion which, emotionally considered, has a high pragmatic value; it imparts a perfect sumptuosity of security.”—William James, Pragmatism and Other Writings, 2014, Penguin Books]

Vivekananda looks at it and says, ‘here we go again!’—this portrayal that all Hindus are nihilistic and transcendental and all the usual Orientalist cliches. And yet Vivekananda used those very cliches for his entry [into the Western world of 1890s]. So it's those contradictions that I wanted to capture, especially for Westerners so that they might look at Vivekananda’s impact in their own society while understanding the dynamics of power that necessarily shaped his message.

But for Indians—and this is even more important—there’s a part of me that thinks I have no right. I know so little, even if I have scratched the surface. I do worry, though, that many Indians talk about him mainly as a ’Hindu revivalist’. I think this is such a narrow way of looking at him. He was also interested in what was ancient and long lasting in Hinduism, especially the discipline of detachment and the highest reaches of moral duty . One may not agree with him, but these were his central concerns. At the same time, he was passionately avant-garde. For example, he believed Indians must take up technical and scientific knowledge, [but] it is wrong to see him as a ‘management’ guru. He was also wearied by the business of organization, even when he acknowledged the need for ‘practical Vedanta’. He was avant-garde in wanting to globalize Hinduism and making the world appreciate its value; and he was avant-garde in encouraging experimentation. Very much like Gandhi he was part of the global idealist movement, whether it's vegetarianism, healing, universal religion. Vivekananda was interested in all of it, even if his relationship to these issues was different to Gandhi’s. That is why he ends up at a place like Green Acre [in Maine], with all the Americans interested in Christian Science, healing, and spiritualism and taught his first lessons in yoga there in a center of alternative spirituality.

Although he certainly did talk of Hindu civilization, and idealized and essentialized it—as he did all other civilizations—he was interested in the possibility of the disinterested militancy that comes from being a sannyasin. That detachment enabled people to operate in the world in a way that that was unusually disinterested. And that's what he thought was primordial and should be spread – hence his novel vision of karma yoga and disinterested service as a way towards transcendence. It is for that reason that he expresses such anger against western racialism and nationalism, which he sees as creeds of oppression.

KS:

One of the remarkable things about the second half of the 19th century was the emergence of these seemingly prophetic figures—towering figures who saw far out into the horizon of possibilities in their own fields—who were also contemporaries. Freud was born on May 6, 1856; Swami Vivekananda was born on 12 January 1863; Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869; and finally Einstein appeared on the scene on14 March 1879. Can we think of these figures as a cohort—i.e., individuals responding to similar set of deep sociopolitical changes that rolled in from 18th century? Perhaps the rise of science, the rise of political domination of the West, and so on? If yes, what sort of underlying currents—or to use Raymond Williams’ phrase ‘the structure of feeling’—were at work by the time Swami Vivekananda appears on the scene? Or is that a level of analysis that doesn’t get us much beyond vague generalities?

RH:

This is a difficult question. On one level, it may indeed be too vague, and in its generalizing tendency raises all the dangers of homogenization that are inherent in global history precisely because you think across cultures too readily or too easily.

But there’s another way of looking at the question. There was indeed a cohort, and there is some point in doing global intellectual history and taking it seriously. In my view, they all sought to encompass relativism within universalism. Although Vivekananda regarded Hinduism and especially Advaita Vedanta as the pinnacle of religion (a view he often took to counter Christian exclusivism), he also opposed conversion and thought that it was a form of coercion. He always said. ‘never take a man away from his or her religion’ because it was a way of robbing people of their birthright. And these men, including Einstein, were all interested in the ethical ramifications of their thought and believed they were seeking ‘Truth’. And yet, all, also, hoped that this Truth somehow would encompass many truths, and especially the relativism that came out of their experiences, investigations, and experimentations.

I think that Vivekananda is especially important because he's the one who most often and very early speaks repeatedly about unity and diversity and the possibility of their interchangeability. They are approaching the society and the world from different perspectives and are searching for meaning in new forms of relativism which are allied in some way to new forms of universal truth.

They are all interested also in the relationship between consciousness and cosmic consciousness.. Freud is also interested in the unconscious of the individual and how it links to universal mythologies, as much as he wants to connect them both to lower levels of reaction and instinct. And that's certainly true of Jung. All were interested in the interrelations between philosophy, the natural sciences, and spirituality. And it's certainly true of Vivekananda as he deals with ideas emerging about the “unconscious” and then translates the emerging psychological discourse into a discussion about “superconsciousness.” How do you deal with what’s deeper within individuals and in cultures and then try to go beyond individuals and cultures? They’re all preoccupied with these questions.

And there is something else—which is that the list only includes men. I say this not to criticize you but merely to say that the lack of women is bound up with the issue about the relationship of authority to exploitation and domination that you raise yourself in the course of your question. Even if you could have come up with famous women to add to the global “cohort,” they would have obscured the many other women who were not “stars” or famous for their accomplishments or philosophies, but were still essential to everything these men did. And as you know, my book tries to show how, without all these women, Vivekananda’s success would not have been possible. The women are co-creators of everything he does—whether it's Sarada Devi and Nivedita in India, or whether it's these women in the West—they help Vivekananda create his spiritual priorities and are models of the ideals that he hopes will move India and the world to greater freedom. I would say that the women have not fully found their place in this history because, almost like the “unconscious” or “superconsciousness”, they were partially veiled from view. And that's why I have tried to reconsider his story anew, not just from his point of view, but also from how they viewed him. Otherwise, we will never get a sense of Vivekananda and his world.

You're laughing at me. [Laughs]

KS:

No, no. I mean, I did actually think about that, but then I couldn't come up with a woman’s name from late 19th century who still matters today in the way say Freud or Einstein matter in their respective fields. In parts that is a challenge of how history has come down to us and how we have been taught to frame historical questions along some specific dimensions and not others.

RH:

Right. That's the real challenge again of this book. I could have written a Great Man history. But I thought, how am I going to write a history of a cardinal figure of the nineteenth-century without writing a Great Man history. And the way I did it was by writing as much about women as about men. Nor did I have to exaggerate the role of gender in their lives, for they were constantly talking about its meaning. Ramakrishna really posed the question of what is a man, or what is a woman. It's wonderful. It is so much a part of our own discussions at the moment, isn't it? And then you have this woman [Margaret Noble, known as Sister Nivedita] at the end, who's much more of nationalist theorist than Vivekananda, and much more of a ‘man-maker’ than her guru. And, at trying moments of her life, she too struggled over whether she felt more like a man or a woman in India and wrote about these struggles with rare insight.

Go ahead.

KS:

No. In some sense, after 1903 when he dies, without her words—perhaps Swami Vivekananda may have faded away from the emergent middle class’s mind. Her reifying of his persona in the public imagination has such a huge part in creating our collective memory.

RH:

It is for this reason that I include so much about Sister Nivedita, for it is almost impossible for us to separate Vivekananda from her vision of him.

One of the problems again—the challenge of the book, which I wanted just to say before we move on to your other questions—is how do we approach the relationship of his key ideas to his own doubts. There are so many doubts in him about: whether he's taking the right path—which makes part of your question [to come later] about why he so often pulled people to the middle way. What I do find so interesting about Vivekananda is that like Gandhi, like Freud—they had very socially conservative views of women. I know less about Einstein, but the others were very disturbed by female sexuality. And that's very evident in their writings. But at the same time—they’re remarkable for the way that they take women seriously. So we have to come to grips with men who hold views of women that we might now find discomfiting but who nonetheless took women very seriously, both as idealizations in their thought but also as practical helpers in their rise and legacy. They can't do it alone. They certainly cannot.

KS:

There is a distinct strand—call it forms of ‘idealism’—that runs throughout 19th century. The German Idealism of Hegel and the Jena cohort, Marx and Feuerbach and Young Hegelians, later Communism as the ends of history, Mary Shelley and her visions of technology run amok in Frankenstein, Humboldt's science journeys, Tolstoy's farms, and ultimately Gandhi's vegetarianism. This is in contrast to world of ‘physicalism’ that manifests through domination & change wrought by colonialism & capitalism, ‘machtpolitik’, of the manliness rhetoric of Kipling to Teddy Roosevelt. You write about Vivekananda’s early life as being “culturally ambidextrous”; but can we think of him as one who was part of this wave of idealism (which manifests in him via Advaita and Ramakrishna) and yet sought to think of society in terms of sociopolitical power, ‘man-making’, “Gita and biceps” and so on. Can his entire life be read as an effort to overcome this schism of the age in which he lived? Is that a fair thing to say?

RH:

I thought about this question a lot, and I do think it's fair, but not a full characterization. It is more complicated because Vivekananda seeks to retain the idealism of, let’s say, Tolstoy Farm, by going to places like Green Acre and participating and re-making global idealism; but also in thinking seriously about what you call ”socio-political power”. Indians in particular talk often about “man-making,” and the “Gita and biceps” and, when they do, they tend to reiterate Ashish Nandy’s interpretation of Vivekananda, which is that somehow he had to respond to the likes of Kipling and Roosevelt and internalise their vision of aggressive masculinity. The mention of Roosevelt is very interesting because when Vivekananda first comes to America in 1893, it's before America is a full-blown colonial power. So it's one of the things that attracts him to that country. It's only in 1898 that America becomes part of “the imperial game”. Prior to this he remarks how wonderful it is not to be among the British, until he gets wiser and feels that he understands more.

But of course, how do we separate out his obvious intense defensiveness about Muscular Christianity and Empire from his view that really Indians needed to have that sannyasin-like militancy. To understand it better, we must focus on the distinction he made between “strength” and “force,” a distinction that Gandhi also made and inverted in Satyagraha., which became “soul-force.” Gandhi looks weak and puny and he actually pushes this self-image against the martial personae of European dictators., But Gandhi, too, uses the word “virility" all the time and could not dissociate strength from some form of masculinity. So that even when Vivekananda wants his female disciples to be stronger and he says to them, “there should be no chivalry because it's a way of keeping you down” [paraphrase]. But he can only think of “man-making” because the gender stereotypes are so entrenched for both him and for the women.

We need to take seriously what Vivekananda said about the difference between strength and force. But there's no doubt that when those ideas of the “Gita and the biceps” come into play—there’s so much overlaying of stereotypes.. He says that [phrase] once in his corpus—and that's what everybody talks about. The idea of the “biceps and the Gita” is so strong and alluring that somebody like Aurobindo sees Vivekananda in a vision in prison when he is held on charges of terrorism. And Aurobindo is inspired in a way that evokes Krishna in the prison-house. Aurobindo mediates because he wants to detach himself and to encourage his radical comrades never to concede to tyranny. So when Vivekananda goes to Mont St. Michel [in Normandy, France], he goes down into the dungeons [of the church-chateau] And looks at the horrible cells and says,”‘what a great place to meditate.” His upper class American hosts hear what he says but they simply can’t fathom the militant edge contained in Vivekananda’s observation.

KS:

Yes, Meditate!

[Harris writes: “His Western followers barely noticed the militant, anti-colonial undertone concerning yogic concentration”]

RH:

And that completely [presages] Aurobindo’s [life], that is Aurobindo taking directly from Vivekananda. But Nationalism and “Indian spirituality” [as an explicit object of veneration], the idea of Mother—all of this is as strong if not stronger in Aurobindo in a way than it is even more alive than in Vivekananda.

This is not to say that Vivekananda did not believe that Hinduism was on the top of the ladder of the world religions being created before, during and after the World Parliament of Religions. I may add that many other Buddhist and Islamic “modernists” made similar claims for their own religions and as a way of resisting colonialism and Christian mission. They had to invert the colonial religious paradigm that Christianity was the universal religion and the pinnacle of religious development, so this preoccupation with asserting the value of one’s religious heritage was very common.

KS:

The flip-side to this phenomena of people taking one fragment of his writing and playing it on for a century is what you have done—You are saying, okay, let's put this statement as part of many other things he said, instead of what is ‘gotcha’ culture of our times. A generosity of interpretation, if you will. But this also leads to us, now in 2022 reading him, being struck by the superficial dissonances of his message. In the West, he called for tolerance of worldviews—i.e., asking the Protestant Evangelism to see the world and its diversities. And in India, he asked his brother-monks to allow “public women” (sex workers) to worship Ramakrishna as their guru. Here, in a sense, like the Buddha, he spoke different truths to different audiences—all in hopes of improving a certain idea of welfare. It almost feels like, if you’ll permit me, he asked the Protestants to become more like the Hindus, and the Hindus to become more like the Protestants. Will you speak to that?

RH:

I thought that was an extraordinary insight you had. Mostly, when people write about Vivekananda and the Buddha—they have Indological concerns [the study of Indian history, literature, philosophy and culture] and hence are preoccupied with tracing metaphysical and spiritual connections. But in asking your question about the Buddha, you may be onto something.. In addressing different audiences in different ways, he seemed to employ the Buddha’s method of skillful speech and to draw people away from extremes.

KS:

upāyakaushala…

RH:

That’s the first thing. But the second thing is the impact of the middle way of Buddhism in his thinking—it is stronger perhaps than we ever realized. Because of this in the West, he’s been seen as a counter-preacher [against Protestant Christianity], against materialism, violence, and fanaticism. But in India, he preached against what he saw as weakness, timidity, and imitation.

And, of course, he scolds! That's why I wrote a section on scolding in the book. The western women found the scolding very difficult. It was really rough, really rough. And he wasn't always sensitive to the gender dynamics on that score. But in India, a guru can scold and a devotee understands that these harsh words are lessons in detachment and discipline. In a monastic institution there's a strong hierarchy of service to elder monks that also worried the western women. They did not always embrace the ethos of service combined with bhakti that shaped devotions to elders and gurus.

I would add though that there is an important difference between a counter-preacher and a “skillful speaker”. The latter suggests skill and compassion and the other adversarial speech. He constantly sought to straddle the two techniques by both scolding and encouraging and, like a “good” guru, prescribing different disciplines for different people.. It’s amazing that he made the monks do dumbbell training in Belur and [François] Delsarte exercises for breathing, whereas he mocked this breathing technique while in America. In the West, he wanted his students to meditate and do exercises that would enhance the pranayama, disciplines that would make them less “busy” and distracted. But in India he wanted an end to what he saw as, in a cliched way, “Bengali timidity.” Because he had idealized and essentialized ways of looking at cultures he applied such techniques to change them. It was this blanket way of looking at cultures, I think, that sometimes may have got him into trouble.

KS:

In Swami Vivekananda’s story nobody is more singular than Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. I don’t know how to describe him—reading you, I am very conflicted. I am filled with confusion on how to think about him. You quote: “He not only meditated, but also cleaned latrines, ate the leftovers of beggars, and touched excrement with his tongue. So degrading for Brahmins, these trials were designed to “eradicate conceit and ego from his mind” and show that all things were mere “manifestations … of the Divine Mother.” His mystical ways included excesses, abandonments, ambiguous ideas on sexuality and gender identities, claims that he was menstruating and so on—and amid all this is clearly a profound religiosity unlike any we see. Later in life, Swami Vivekananda describes his early views of Ramakrishna as “brain sick baby”. But before we go further, historically speaking, is Ramakrishna an almost singular persona—in that, he doesn’t seem of a type that frequently occurs in modern Indian religious histories. Or was he merely part of these periodic manifestations of these kind of guys who appear to break down every barrier—socially and cognitively—there is.

RH:

I think it's the latter. For a person who's a novice, like me, to encounter Ramakrishna was remarkable. Many may think of him as strange -- but I think he's remarkable. Of course, he's also disturbing because of the stories of his life-defying spiritual trials. And he may even offend contemporary sensibilities when we encounter the discomfiting tale of his Sarada Devi, his wife – she lived in a tiny space for years near the temple of Dakshineswar. I would say that Ramakrishna is rare but he is not unique. There are other famous Hindu mystics, hence why so many, who saw him during his trials, thought he was similar to Chaitanya. There are precedents in Hindu tradition to Ramakrishna, even if he crafted his message in his own way.

But Vivekananda is unique! Vivekananda is unique is because he globalizes Hinduism. And whether that's good or bad is open, and remains open, to debate. At the time, of course, the Orthodox hated what he was doing—the whole idea that one would engage in the world in the way he suggested was a terrible transgression, especially for a sannyasin. He seems at intervals to be almost worldly in the way he institutionalizes, and yet his vision was often radical, and its articulation unprecedented.

Ramakrishna seems strange above all because of his insistence on being a baby. But the way he became a baby spoke a kind of cosmic truth. He emphasized babyhood precisely because it was a universal human state, before religion, culture, and hierarchy imposed their transformations. And created diversity. And this understanding or intuition—whatever you want to call it—was extraordinary. And yet it’s integral to many “Hindu traditions, “ both in its openness to other paths and in the way it sought to envelop and encompass those traditions.

KS:

But then there’s a deeper, or harder, question that I have thought about with no clear sense. My previous question was, in some sense, about the external aspects of Ramakrishna—all that he did in the world. But there is a deeper and more profound thread of love and compassion that Ramakrishna shows towards the world and instructs Vivekananda to see things differently. There is that episode about Vivekananda mentioning kirtan music having no rhythm but Ramakrishna corrects him, helps him see something deeper, emotional: ““What are you saying! There is such feeling of compassion in them—that’s why people like them.” It is as if he wants to remove from Vivekananda the burden of reason: ““As long as there is reasoning, one cannot attain God. You were reasoning. I didn’t like it.” This is very far from the world of Brahmo Samaj or colonial Christianity or middle class Bengali life. Was this ability to demonstrate the ‘radicalism’ of love itself—a self-devouring sublimation, if you will—that ultimately brought Vivekananda to Ramakrishna? A love that is so transparently attached and eager to bring you within the fold. And I'm sure Vivekananda didn't experience that kind of love at home—as one of the many children at home. Is that how you see it. Is it love, in its multidimensional and cosmic sense of the word?

RH:

Yes, absolutely. And I really believe that it's hard as an historian to talk about these passions and relationships and yet theyare central to my account. Historians often think such questions are outside their purview – they would say that “love” cannot be the center of historical enquiry. They might feel that “It's so airy, fairy, it's so touchy, feely.” But in talking of Ramakrishna’s love for Vivekananda I am only reiterating what Vivekananda said himself:—[paraphrase] “no one loved me like this not even my parents.”

[“S[wami]. How I used to hate Kali and all Her ways. That was my 6 years’ fight, because I would not accept Kali.

N[ivedita]. But now you have accepted her specially, have you not, Swami?

S. I had to—Ramakrishna Paramahamsa dedicated me to her. And you know I believe that She guides me in every little thing I do—and just does what She likes with me. Yet I fought so long.—I loved the man you see, and that held me. I thought him the purest man I had ever seen, and I knew that he loved me as my own father and mother had not power to do.”

“—Sister Nivedita, The Master as I Saw Him, 1910”]

He constantly remarks how this love was transformational and how it changed his life. And you know, you feel the sincerity of this. So there's that. There's also the responsibility. Ramakrishna's a baby and he says, you must take care of me. There is a filial connection that inverts the guru-disciple relationship and confirms it at the same time.

KS:

Despite their ages being the opposite. [Ramakrishna was born in 1836, Vivekananda was born in 1863]

RH:

That is the whole point. Ramakrishna is obsessed with inverting what is ordinary. That's the whole thing about him.

But there's also the promise. And this is something that I think that in a secular age is very hard to grasp.The promise that Ramakrishna will show Vivekananda the way to see God. It's about attaining darshan, which is what Vivekananda craved. And there's a wild, but also persevering ambition in this search that Ramakrishna exemplified. Vivekananda came to believe that Brahmoism and its sedate rationality simply could not offer such transcendent experience. Brahmoism also evoked in him a sense of terrible loss—because Indians had to give up so much, including family traditions and images.

What Vivekananda is saying is yes, there's the unity and formlessness at the top. But he's also saying, on another level, you don't have to give up anything. You can have all your devotions. You can do everything as long as you don’t confine yourself to a foolish “don’t touchism,” which he regarded as inane and almost against “true” spiritual searching . And that's why I argue that his connection to Ramakrishna isa spiritual reconciliation of the highest order for him. You don't have to throw away or discard what you love. It is also a way of saying—I don't need to accept Western universalism, I don't need to believe that rationality is everything, which is why love plays such an important role in his thought. He always said he was a severe Advaitin, which is to say that he's very intellectual, but he also kept on talking about how he was, underneath, a bhakta. He also acknowledged that without Ramakrishna, he wouldn't have done anything. He just would have been a Brahmo in Kolkata, and he would have been smart [and successful in life]. But you know, he wanted more than that. He really did. And I do think ambition plays. Spiritual ambition is powerful. We must imagine it.

KS:

When talking about Ramakrishna and Vivekananda—a narrative technique you use is to offer them as antipodes. As dualities in tension— reason and experience, masculine and feminine, empiricism and mysticism, and so on. To help explain this better, you try to present a different sort of model, a kind of historical model of how to think of two men who ‘feed’ off each other. An interesting comparison you have is Vivekananda’s St. Paul to Ramakrishna’s Jesus.

RH:

Yes!

KS:

But then I thought about it. And I said, but what if it was different: What if it was Ramakrishna’s John the Baptist and Vivekananda’s Jesus. Is that not possible. [Laughter] Instead of Vivekananda evangelizing on behalf of his master; it is Vivekananda who is the Master for our new age, and Ramakrishna is just awakening him to his destiny. What do you think?

RH:

[Laughs] I don’t accept the St. Paul analogy and that's what I say. But many people talk about him in that way. And I think that there's a tendency to do that because they see the Roman Empire through the lens of the British Empire. You go and you preach. And you get rid of “Jewish superstition”. Well, here you get rid of “Hindu superstition”. So you bring the Brahmo-ism in, but then you remake it with Advaita and these new forms of yoga. But these arguments only tell part of the story.

I do believe though that Ramakrishna gives Vivekananda the confidence to go abroad. Ramakrishna gives him the confidence to say—I can transform this tradition and make it a world-moving tradition. I think that's what Ramakrishna does for him.

KS:

I don't know if you've written a book on [Albert] Schweitzer, but I read that long essay that you wrote. Obviously you’ve written about Dreyfus [Dreyfus: Politics, Emotion, and the Scandal of the Century]. And then now Vivekananda. These are all men who are at some level within the “establishment”, but then for whatever reason are cast away, walk away, voluntarily go away. And through their lives, you write these vast histories of an age itself by turning their lives into keyholes through which we can see much more than individual lives. I don’t know if that it is intentional or if you are naturally attracted to the stories of individuals who presage something momentous. For Dreyfus it is easy to see, his life story presaged the great wave of antisemitism that engulfed Europe in 50 years thereafter; for Schweitzer, it was the coming to fore of global campaigning which took ethical positions seriously. In 1903, when Swami Vivekananda died, was there a sense that his life’s work contained something momentous that was to emerge? If Hindu nationalism hadn't come up as a political movement—would he be understood completely differently? Or was he just simply preparing the grounds for Gandhi to emerge in a different form.

RH:

Tricky. I mean, what I always wonder is if he hadn't died of 39. You asked the question [when we spoke earlier], would he have been political.

KS:

[Laughs] I was thinking of an alt-history novel. That was just an idea.

RH:

It would make a good novel. But the thing is—would it have been Vivekananda instead of Gandhi? If Tilak hadn’t died, would it have been Tilak instead of Gandhi? Would Vivekananda’s views on Islam have changed? Would he have reacted like Gandhi to Dalits? Or would it have been something different? And I think, all of this is up in the air. And that's why I think he's such an enticing but also provocative figure because he pointedly raises all these issues. And then we don't see what he does with them. He dies.

We're left instead with this woman [Sister Nivedita] who many people thought was a crank, though this is another unfair and reductive characterization. [She’s also] another person [on the] outside. Really outside in many ways who reshapes his legacy. I do think that he was more committed to universalism and harmony than people realize and that these aspects of his thought have now become effaced. I have told that Nehru was present when Ramakrishna Cultural Institute in Calcutta was opened, and I don’t find that surprising. There's been this shift [in how generations perceive him]. He's a movable feast—literally—because you can find anything there. And that's also both the magic of him but also why he's so disorientating, and provocative. There are times when he seems to presage our views and other times when he seems reactionary. Just recently I re-read how he raged against the British for their murdering of the Aborigines in Australia, in Africa, and in America—earlier on he was much more critical of the Native Indians not leaving any “civilizational” traces. But later, he was unequivocal in his condemnation of these genocides. He is simply appalled by the what he sees as the inherent violence in Western Civilization. And that's a very Gandhian notion. Except, unlike Gandhi, he does not repudiate science, and he does not repudiate technology. And he does not repudiate anything that can bring people up. These differences are important.

KS:

This is a complex question to ask—does the death of Ramakrishna make Vivekananda free? And I don’t use “free” in a casual or colloquial sense we use everyday; nor in the biographical ways we see in your book—by which I mean Ramakrishna’s death allows Vivekananda to go from being a Bengali to becoming an Indian? Is that a right way to frame his life. But also, “free” in a deeper sense: to going from becoming a middle class acolyte of mystic to somebody with his own ideas, his own sense of what constitutes universalism, to experiment and somebody with his own impact in the world. In a Hindu way of thinking, when the Guru recognizes the student is ready to be on his own, the Guru leaves the scene. So in that sense, did Ramakrishna die at the right time so that Vivekananda could flower?

RH:

I think he did. Ramakrishna did do some traveling, but it was Vivekananda’s continental pilgrimages, up and down India, that transformed his ideas and broadened his experience. He picks up his first disciple [Sharat Chandra Gupta, or Gupta Maharaj, who later becomes Swami Sadananda] in a train station [at Hathras]. It's significant. Sometimes he’s on foot and especially when he goes to the Himalayas. But pften he's traveling by train. It means that the freedom struggle in India is part of this [economy of] trains. How people become “Indian” through the trains—we know it also from Gandhi’s biography. Vivekananda doesn't write much about these travels. But yes, I think the travels astonish him. I think he really is overwhelmed by the diversity in Indian society and by the religious possibilities. And by the fact that his observations make him take a more coherent stand against the British. The British kept saying “you'll never be a country because you're so diverse.” That's the importance of [his] message—Diversity is what makes us strong. It is one of our many unities. That's where you have quite a shift from the theological into the ”political.”

When I hear Westerners talk about diversity, I see often a sanitized idea. But when I think of diversity, I think of India. It's less now, but that there are so many Indians who remembered living in a very diverse society and finding real identity in that diversity.

KS:

I think there is a book clearly to be written about how trains made ‘India’. And I'm talking not in the Post- independence world but in the 1830s to about 1930, when things like price volatility transmitting shocks becomes a reality: if grain doesn't arrive in Calcutta, then it is crisis in Madras. Along with it comes hunger and everything else follows including. So a national consciousness is built by this transmission of shocks—particularly mass starvation.

RH:

But don't think Vivekananda wasn't interested in that [political economy aspect]. They were all interested in that because of the famine. The famine rocked him to the core. He kept on telling them, you know, love God in the terrible, and so on. But when the famine struck and then the plague—the plague he was able to face better. But the famine really troubled him. Do you see what I mean? And I think you're right. Famine helped create a national consciousness of the irredeemable evil integral to colonialism. That's my personal view.

KS:

The strange thing—perhaps not strange, but one of the most extraordinary things I realized from your book is how frequently in bad health most of Vivekananda’s fellow ascetics and he himself was. Dysentery, hunger, bronchitis… And you mention that Swami Vivekananda “was chronically ill for much of his adult life, and so his body also intruded on his spiritual mission”. And amid such weakening bodies—often due to rigorous and “pitiless” austerities—Vivekananda creates this idea of “man making”. A discourse of strength and masculinity tempered by the feminine, and an heroic ideal of man. How do you reconcile these distinct strands?

RH:

For me there's such pathos in the remarks about robustness and masculinity, because he's so sick. And you're right. He prescribes meat eating, but at the same time he also says its wrong—which is fascinating. He says, I know it's wrong. But he says, we must eat meat because we must be strong. He has a fascination with Westerners who eat meat. That's why he prescribes it almost as medicine. It's basically you do whatever you can to be strong. That’s why the whole story is so difficult—because he says to Josephine MacLeod, [Paraphrase]“I'm organizing a monastery, I’m building this, I'm doing that. But I really want to go back to sitting with Ramakrishna under a tree. “[Laughs]. There's that side of him which still sees himself as looking for God. But he realizes that you need harsh measures to fight against these people [British colonialists] who will make you sick and hungry. It's not surprising that he talks about ‘Practical Vedanta’.

KS:

It must have been such a difficult time.

RH:

Yes. When he comes back from one of his places where he’s convalescing to do the Plague Manifesto [read here] in Kolkata because he wants to do it. He realizes that what's the point of devotions and puja-s if your people are dying in the streets.

KS:

We briefly mentioned Christ. Other than the Goddess Kali and Ramakrishna, it almost feels to me that the other person who constantly figures in his thoughts is Christ—almost as a foil, a rival, a benchmark. He translates a 15th century text called “The Imitation of Christ” into Bengali in 1889. But he seems to have many disagreements with the Protestant sects who come to India as missionaries. How much of his profound disagreements with them was theological and how much of it was a sense that they were agents of British colonialism in one form or another? i.e., Can we divorce Vivekananda’s antipathy towards religious conversion from the political context in which he lived?

RH:

He fancies that Christ and Buddha were probably in the same line of incarnation. So it's not Christ that he finds problematic. That's right. On his travels he takes along both The Imitation of Christ and the Gita. He esteems the first because it teaches the way to be a sannyasin but also indicts missionaries for not imitating Christ. The Imitation of Christ is a book about humility. But later, his view of the The Imitation of Christ changes completely. He says “Don't imitate Christ. Be better than Christ.” The worst thing for him are Indians who ape the British. He despises them.

He's fascinating on this later interpretation. And I'm writing about it now. I'm writing a new book on Jesus in India.

He sees Jesus certainly as an avatara,. He thinks Christianity is an advance on Judaism and Islam because at least Christianity acknowledges that the human is divine through Christ. But he also says that Ramakrishna surpasses Christ; and above that is Advaita or formlessness—all of this is nothing compared to the union of Atman and Brahman. With Advaita, there are no religious symbols, no sects, and for this reason Advaita is the umbrella under which all religions may shelter. So that's how he thinks of it. He's despises Christianity as an institution but he is certainly not against Christ. The material on imitation is very interesting. He argues that [paraphrase] “imitation is good, but it only takes you so far!” You have to invent. It's about originality. He does not want Indians to copy other people's traditions. He doesn't like it.

KS:

I wrote a piece on imitation and Gandhi a while ago. It is about guys who mimic Gandhi, such as Vinoba Bhave, and there's a whole group of such people—perhaps less so now. But out of mimicry, they argue virtue emerges in them. There are devout Muslims who, for example, put henna their beards because they believe that the Mohammed used to do that. Through mimicry and emulation, virtue is believed to be born.

RH:

I'd love to see the Gandhi piece you wrote. About imitation—it’s very interesting.

KS:

Yes. I'll send it

RH:

Yes, yes, send it to me.

KS:

It almost feels like we are setting up stage for Vivekananda to emerge on the global scene. And but just before that he arrives in Madras. There is very interesting line you have: “Madras, not Calcutta, provided the first lay nucleus of support for Vivekananda’s emerging view of national revitalization.” — What was it about the south of India that awakened Swami Vivekananda to a kind of national revival?

RH:

I think there needs to be a book on this, but not just about Vivekananda, but also how people come to the south from the north and then begin to think differently about India. He has a very

interesting piece: he calls it “Aryans and Tamilians.” And we all think that he adapted all the racial categories that were invested in Aryanism. But since he wasn’t that interested in Theosophy—where Blavatsky spoke at length about “root races”—it’s not really the case. He doesn't. He's also very often very suspicious of racial categories—instead he argues that Aryans and Tamilians are merely philological categories.

He’s trying to build bridges and that's why he has such close connections with Southern Rajas. Did you notice that when he comes back…

KS:

And there’s was Alasingha Perumal earlier…

RH:

So there's a whole nucleus there in the South— of people, thinkers. We must ask the people who really know the context of the Madras Presidency to tell us more about this world: how much is he really the one of the first public intellectuals in the south? Because, from my list, Gandhi goes there…they all go to that place afterwards [after Vivekananda]. Is he the first, is the one who in some sense “creates” this idea of traveling to the South among northern ‘intellectuals’. Do you see what I mean?

KS:

I suspect Madras or the South has a catalyzing effect on many North Indians thinkers and intellectuals. You write, “Whereas the elites of Madras sneered at Vedas and Vedic seers”, he challenged them to test the ““science of the Rishis” to determine its value”. And yet, he was also against ritualism and cautioned and hectored against it. It almost feels like his modus operandi was to bring people to the middle—neither dismissive of the past, nor blindly wedded to it.

RH:

He also sees the South as providing those traditions of Bhakti that are essential to broader Hindu consciousness. And again, these are not part of the cliches of who Vivekananda was because, you know, he seems a jnaani. But he admires all these things. And he talks about it all the time. And yet—I didn't have time to explore it enough—but I do think from the minute he goes on those travels, this idea of the India [begins to take root]. There are those who suggest that Dakshineswar where Ramakrishna lived was already a miniature version of India because it was on the crossroads of so many pilgrimage routes.

KS:

I don't want to dwell too much on the Chicago conference because a lot of people have written about it. But, I have a very prosaic question. Did Vivekananda need a visa to go to America?

RH:

[laughs] No, he didn't. I was thinking about that. I don't think he did. I'm going to JLF and am struggling to get me and my husband an Indian visa!

KS:

[laughter] So much of the Vivekananda story in the public imagination hinges on the 1893 Chicago appearance. Why does it matter so much—I don’t mean this facetiously. But rather, why does it capture the imagination of India particularly? In America, I can understand—he has that element of exotica and thrill. But why does it matter in India? Even today when I talk common people and say, Vivekananda, they may not know much but they know the Chicago conference.

RH:

I hope you don't think I'm being flippant here. For Indians, it's the pleasure of this guy coming and telling the Americans “what for.” I think they just love it. He gets up at the Parliament and he does everything that is unexpected. First of all, he looks unique because he's created this wonderful costume for himself, so he doesn't look like a sadhu. But he doesn't look like a Christian minister; he is wearing this flamboyant garb.

Then he says to them and keeps on saying: How can you call us Heathen? Basically. Look at me. Look at me. I am not a heathen; I am not inferior. And that's a trope that many Indians [of that generation] spoke about... It's not just Vivekananda. It gives an ‘edge’ to what they are saying. There's an emotional pleasure in the idea of a man unexpectedly taking the platform and saying all these things that they might have wanted to say themselves. Do you think that I'm wrong? Am I?

KS:

No. I think there's a certain pleasure in telling the white colonial master, he is wrong while being beholden to him in all other aspects of life. That’s definitely going on. But I mean that others have done similar things in different settings—Gandhi goes to a court and he tells a judge about why he is now an “uncompromising disaffectionist and a non-cooperator” and that he should indeed be imprisoned. But none of that has this ring of mythology and grandeur as the 1893 conference.

[Gandhi at the Shahibagh Courts in Ahmedabad, 1922: ”I owe it perhaps to the Indian public and to the public in England, to placate which this prosecution is mainly taken up, that I should explain why from a staunch loyalist and co-operator I have become an uncompromising dis-affectionist and non-co-operator. To the Court too I should say why I plead guilty to the charge of promoting disaffection towards the Government established by law in India.”]

RH:

I think that's a good point. The exposition in Chicago, with the Parliament that runs alongside it, is an announcement of America's entry into the world as a great, and then the greatest, power. And I think that's why. It's one thing to do that in South Africa, and it's another thing to go to America, to Chicago, in the place where they're killing cows in the millions, literally every year. And say your piece. It’s literally like speaking truth in Babylon.

KS:

The interesting thing is in that conference—and I think for the remaining years of his life—next to him is Anagarika Dharmapala. There's a stamp issued by the Indian Government on Dharmapala, but few people know him. He is often seen as a father of Sinhala nationalism. And some think of Vivekananda as a father Hindu nationalism. And there they are, these two guys, sitting on a stage in Chicago—trying to figure out what to do next after saying their piece. What is the relationship between Anagarika Dharmapala and Vivekananda. Who was he and what was the relationship between the two like. You write that “Dharmapala’s diary, for example, contains disapproving remarks about Vivekananda’s enthusiasm for champagne.” You also mention that, “The newspapers spoke of Vivekananda’s handsome and imposing presence, as well as his command of English. After the Parliament closed, he built on his reputation and on the contacts, eventually easily eclipsing Dharmapala in his fame and influence.” As they say in teenage circles, were they ‘frenemies’—not sure if you know this TikTok and Instagram generation term—where their friends and enemies together.

RH:

[Laughs] Frenemies!It's really interesting, because when I first started this work, I started on Dharmapala. Then I read his unpublished diary in Sri Lanka—and he has an extraordinary diary. And I couldn't bear it. Dharmapala really is antisemitic. He really does absorb Western racial theories. He, unlike Vivekananda, has no guru, though he is a mystical aspirant. Instead he focused on the Theosophical Mahatmas, [imaginary Masters], who are deemed to live somewhere in the Himalayas and whom he has never met. And so there are many aspects of him that were very difficult. Although the diary throngs with people and associates, Dharmapala was lonely in a way that Vivekananda never was. Also he's also much less intellectual than Vivekananda. And he is, in many ways, the father of Sinhala nationalism.

They were definitely “frenemies”! But what goes on between them is that Dharmapala doesn’t accept Vivekananda's appropriation of Buddhism within the Hindu fold. And Vivekananda sees the Sri Lankans as inappropriately Western, overly Western. He also does not accept the kind of purity campaigns [by Dharmapala], which emphasized teetotalism. Vivekananda on occasion smokes cigarettes and drinks champagne. And Dharmapala spends his life complaining about him. And Dharmapala also is very jealous of Gandhi, as his diaries reveal. Dharmapala is a Sri Lankan, he's Sinhalese, but he lives mostly in Calcutta, and he trying to compete in the Bengali cultural world.

Whereas Bengali culture is Vivekananda’s birthright, Dharmapala wants to re-convert the sub-continent to Buddhism and to make an impression in Calcutta where he remains an outsider. Dharmapala is equally global, though. But whereas Vivekananda goes West, Dharmapala goes to Thailand, Cambodia—all these other places—and especially Japan, where he hopes to spread his Buddhist Modernism. Whereas Vivekananda makes a a greater impact in the West, even if it’s diffuse. Dharmapala can't get anyone except his family to bankroll his enterprises and an Hawaiian woman named [Mary Robinson] Foster, who basically is the great contributor to all his efforts. So it's a very, very different trajectory.

Also Dharmapala detests Hinduism, though he keeps it always under wraps. He talks about going to Benares and he's disgusted by the ritualism and what he saw as its sensualism. Vivekananda never had that view of different forms of religious experience. They are true frenemies. I must say, Vivekananda never says a bad word about Dharmapala (except to suggest that Dharmapala is not a great speaker)and later on he doesn’t mention him because he is not very concerned with him. Whereas Dharmapala continues to care about Vivekananda [laughs].

KS:

The irony is that this. Your description sort of reminds me of many stories where the Buddha has critics and enemies for whom the Buddha becomes the sole locus of their antipathies. But the Buddha never reacts to them, and he just goes on with his life. And in some sense the fact that Dharmapala was a Buddhist—his story was mimicking this part of Buddha’s life— makes it a kind of double-irony.

RH:

And that's very interesting what you say because, of course, for the Westerners—Vivekananda was a reincarnation of the Buddha, especially because of his rotundity and how he looked when in contemplation. Dharmapala though also did a lot of meditation and often in public places in Bengal to show people how you could be detached. Despite thise exercises and disciplines, howwever, I believe he was much more tormented than Vivekananda.

KS:

There’s a teacher in Southern India [Nochur Venkataraman] who's written a book on Shankara and in there there is a small description on Vivekananda. And in it, a foreword says that Vivekananda had ‘the mind of Shankara and the heart of the Buddha’.

RH:

He keeps on saying that one needs heart of a Buddha—you need to have both intellect and heart.

[Swami Vivekananda in ‘Jnana Yoga’, Chapter VI titled ‘The Absolute and Manifestation’, London, 1896. ”What we want is the harmony of Existence, Knowledge, and Bliss Infinite. For that is our goal. We want harmony, not one-sided development. And it is possible to have the intellect of a Shankara with the heart of a Buddha. I hope we shall all struggle to attain to that blessed combination."]

But that's again about—unity and difference, unity and opposition. And that's what he says to the Muslims when he thinks of a unified India and calls for the partnership of a Hindu brain and a Muslim body. I've begun to wonder anew about that famous quotation and think that it might express more than hierarchy within holism.. Perhaps there was an unconscious admiration for the “strong” Muslim body. His relationship to Islamic force—the fighting, martial tradition—was ambivalent. He is both very condemnatory of it as you'd imagine, but he regards it as much less horrific than Christian force and imperialism.

KS:

I was basically coming to, I suspect, the part of the book that most people would be puzzled by. The complex relationship between Vivekananda and these interesting American women. Early on in the book, you write that “ocean liners brought the ideas that confounded North American women with ideas about God that diverged from their childhood Christianity and exposed them to the first reasoned cases against imperialism and their own civilization.” And then later in America, we hear about Swami Vivekananda’s extraordinary popularity with a certain kind of female admirers: rich, white, socially engaged, from New England. One of the American woman, Kate Sanborn, later describes herself as an American Desdemona and him as a Bengalese Othello [she doesn’t mention how Othello ends!]. Another, Constance Towne writes, “I thought him as handsome as a god of classic sculpture”. Can you briefly tell us about this seemingly improbable dance between an Hindu monk and American women? Is it a form of Orientalism at play, or was there something deeper?

RH:

Well, I glad you picked up this stuff on Othello because I was gonna write much more about it. But I wanted to keep the narrative [of the book] going.

KS:

I’m sure there's so many times you must have done that—left stuff out to keep the book coherent.

RH:

But Othello is more than once. Othello was a tragic figure. He's a good man who is misunderstood because of his race. They see that. But at the same time it's played by an Irishman who blackens his face. And I can't remember the name of the actor. [John McCollough] He’s very famous. And they've all seen this play. And so Othello is a way of thinking about somebody who's black, who's dark—but who isn't a Black American, but might be Irish. These conflicting images and possibilities suggest a lot about their imaginations.

How they can think of him in that way when, of course, Othello’s tragic flaw is his jealousy over a woman—when that's not the place where Vivekananda is meant to be. So his relationship to these women is not easily reduced. On one level a social historian might say, “well, they team up because of mutual resentments, they’re not at the top, despite their spiritual and intellectual “superiority.” I think they do have mutual resentments , but there is much more than that that binds them.. They love him and esteem him because he is different, because he encompasses a set of qualities that they have never encountered in a single man. They're attracted to him. But above all they love him because he listens to them. He seems to combine a kind of Bengali “femininity”—he is musical, he is sensitive, and he cooks for them – that makes him so wonderful. They are amazed by the way he grinds his own spices, and wants to introduce them to the Indian culinary world and share its tastes with them. And, all this with the intellect. It's that combination. So they feel they've actually found somebody who is bringing together the opposites. That is amazing for them.

KS:

What I am also interested is the key counter-question—what did Swami Vivekananda learn about women after encountering his American hosts. He describes among these women as ““I am, as it were, a woman amongst women.” He draws some social lessons as well—he writes: ““Many men here [in America] look upon their women in this light. Manu [the ancient Hindu lawgiver] … has said that gods bless those families where women are happy and well treated. Here men treat their women as well as can be desired, and hence they are so prosperous, so learned, so free and so energetic. But why is it that we are slavish, miserable, and dead? The answer is obvious.”

RH:

What does he learn from them? What he learns from them is everything that he knows about the texture of American society. How to act. Who to ask for donations. His understanding of Christianity is enhanced. Everything he understands about healing and alternative American Society. He learns so much from these women who have experimented with everything and then find the answer to their spiritual questing in him. So he learns the whole smorgasbord of the American Idealist movement from these women. And the only thing he repudiates is the vegetarianism, even if he often teases them about the fads and fashions of alternative American spirituality. He says, I must have meat, I have work to do. But I really believe that the need for meat was because he was always feeling tired, always feeling sick. And he had a very literal sense that the blood and the flesh would give him strength.

KS:

What I didn't know was the fact that William James ends up quoting and referencing Vivekananda in the text and footnotes of his book(s). Then, after I read you, I went looking for them and yeah he does quite extensive footnoting of Vivekananda. And then there's Max Müller, who is a more complicated figure in today's present day India, because he's seen as sort of the acme of Orientalism and Orientalist scholarship. But for Vivekananda, Müller was like a great friend and an interlocutor of ideas. So, there is this remarkable triad: William James the American psychologist, Swami Vivekananda the Indian monk, and Max Muller the German Orientalist who come together—quote each other, reference the others works—to do two things. They turn Ramakrishna into an embodiment of Hinduism and they elevate Hinduism as a field worth of academic enquiry. And in turn set the stage for the next generation of philosophical minds—S. Radhakrishnan and Surendranath Dasgupta and others. Is that a fair characterization?

RH:

Yes. That's the short answer and I would agree with you. But I think why this is important is that without Max Müller, there would be no Ramakrishna in the West. It's Vivekananda who gives the material [to Müller for “Ramakrishna’s Sayings”] and the Sayings are translated badly by Müller. And in those sayings—in the introduction, Müller also makes a serious critique of Theosophy as nonsense, which is something that Vivekananda does privately. He cannot criticise publicly because he is trying to get people from Theosophy into Vedanta. But when Müller makes his case for him for talking about Ramakrishna as a“Real Mahatman,” Vedanta gains respectability. And so it's very important.

The debate with James is, in my view, even more interesting. Because, in a sense, my book owes everything to Rolland’s[Romain Rolland] discussion of Vivekananda. He wrote about Vivekananda [La vie de Vivekananda: Et l'Évangile Universel, 1930]. In this, there's a whole discussion of James, and it's this extraordinary encounter between a haughty French intellectual and his realization that there can be an American intellectual. [laughs] He writes about William James and he sees that this is part of global discussion. See? So that's where I got it from. Without Rolland, I would never have made the connection between James and Vivekananda in the same way. It was extraordinary.