INTO THE WORLD OF A RELUCTANT ICON

Photo by Johney Thomas, The Hindu Archives

The air in Edappal, the town in central Kerala where ‘Artist’ Namboodiri lives, was dense. The heavy humidity of that spring evening encouraged lethargy, as was even the case for Namboodiri. Submitting to precisely what the weather demanded, he sat shirtless, with his lungi folded up to the waist, relaxing in a reclining chair. The tiles beneath our feet were cold, a reprieve from the day’s heat, so I decided to sit on the floor, by his side. My friends who accompanied me to see him, Majeed and Madhu, the second of whom was Namboodiri’s nephew, sat in the chairs facing him. He had agreed to meet us, despite not being in the best of health. His voice trailed when he tried to speak loudly.

Madhu asked him about the recently-released documentary on his life by the award-winning director Shaji N Karun, who is often considered one of India’s greatest filmmakers. “Ah yes. They are doing something… ” he said. Karun’s debut film Piravi won the Caméra d’Or at the 1989 Cannes International Festival. Unprompted, Namboodiri added, “He has a great visual sense.”

I could not help but smile at his observation. The ‘visual sense’ of a filmmaker was clearly what appealed to him. Once, while Namboodiri was on a sabbatical from his drawing and painting career, he worked with iconic director G Aravindan, and in that short career won the Kerala State Award in art direction. He never really pursued that line of work, and soon returned to his first love: drawing and painting.

My cup of tea had gone cold. I decided to take a photo to remember this evening with Namboodiri. On seeing my camera, he was suddenly reminded of some unspoken code of sophistication. “Should I wear a shirt?” he asked.

His 86-year-old body is surprisingly well kept: his muscles are still taut, his skin is leathery and has worn well with age, his luxuriant silvery hair was tied up into a ponytail, and his spectacles dangled off his neck.

“Let it be. Unless the mosquitoes ...” I had vocalized what he instinctively knew. He smiled and shrugged. He knew these mosquitoes. He was yet to draw them on paper, as far as I could remember from his work, but, he was watching them flit by, just as he watched my friends, me, our conversation, the cup of tea, the changing light in the skies and the children running behind cars on the street. So shirtless it was to be. I wandered about and took photos while they continued to talk. Noticing my lens focus on him, he sighed, and said, “What an astonishing thing. It might just rain in February!”

From the outskirts of his estate, he looked like a sagely apparition, with streaks of light peaking through the copious shade of trees. A pale, aged figure who watched the world rise and fall. If the details of his persona were obscured—his wrinkles smudged into a suggestive inchoateness, a few stark lines for the lower body, a sweep of dark shades for the torso and a swish of an arc for the tuft of hair—he would resemble his own innumerable and much loved line drawings.

‘Artist’ is not an appellation he is fond of, no matter how admiringly it is uttered. “To be honest, I do not know why [they call me an ‘Artist’]. I have never called myself one,” he said in a recent interview. “Moreover, I don’t even like being spoken of as such … I dislike it.”

At home with Namboodiri, photo by Keerthik Sasidharan

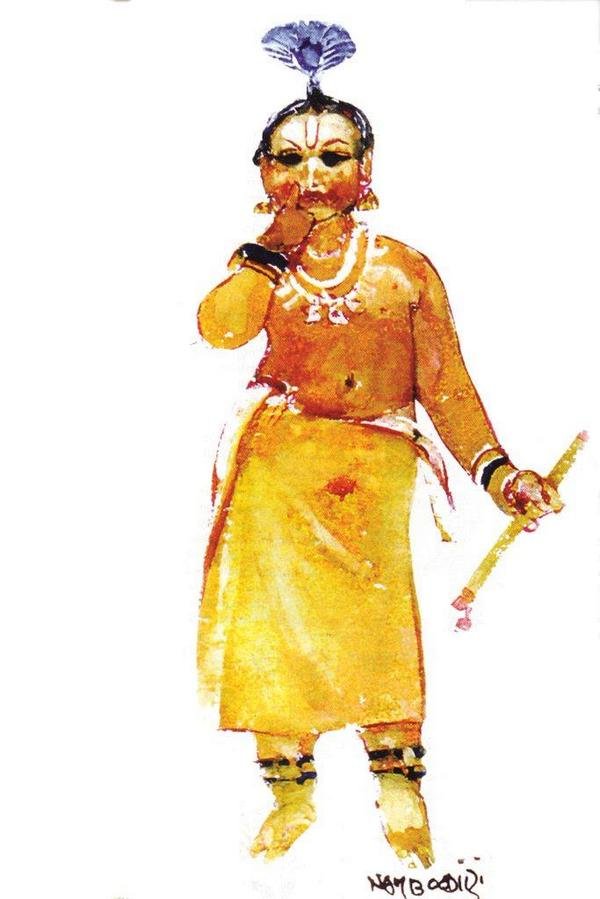

The implicit burden and pretensions of grandeur that come with the title stifle him. Perhaps, in an old fashioned way, when he looks back at his teachers and peers—KCS Paniker, Dhanapal, KM Adimoolam and others from the early days of the Cholamandalam Artist’s Village in Chennai, bright stars in the artistic constellation—the ‘Artist’ tag conferred on him seems facetious. But it has stuck. Kerala is stubborn that way. In the past, others have called him ‘Illustration’ Namboodiri. What kind of a Namboodiri is that? asked his friend, collaborator and satirist VKN mischievously. His canvases and sketches are signed with ‘Namboodiri’—tightly written in capital letters with a fleshy dollop above the ‘i’. There is a certain irony in the association between his Brahminical name and his artwork. Especially as his work continues to struggle past the orthodoxies of the varna system in search of themes and inspiration. It draws from the hurly-burly of life in Kerala: the folly of the highbrow pretenders, the sly desperation of the commoners, the sprawling decay of urban life, the patiently crumbling temples, the overworked elephant amidst the cars and their exhaust, the roll of fat that bulges out of a prostitute’s ill-fitting blouse. Life on this wet sliver of southwestern India, in all its vividness, is the ink in his pens: irrespective of whether it is profane or puerile, secular or sacerdotal.

As a talented young man from interior Kerala, Namboodiri was first exposed to the wide world of artistic possibilities during his early years of training in Chennai. At the Artists’ Village, he spent his days amid great painters and sculptors who had been at the forefront of artistic responses to India’s socio-political realities: the long shadow of colonial art, the fervent responses by the ‘nationalists’ from the Calcutta group under Abanindranath Tagore, the post-Independence art movement of the Progressive Artists Group under MF Husain and FN Souza and, finally, the experimental efforts of the Baroda school. In those days, young Indian painters either headed to Paris or to the big Indian cities. Namboodiri returned to central Kerala where his future was, at best, uncertain. His training under KCS Paniker, however, stood him in good stead. Under Paniker, a new world of aesthetics opened up to Namboodiri: one that reached beyond the classical paradigms of Ravi Varma or European Renaissance Art, where he could unashamedly reflect on the fluidity of folk art or the stuffiness of temple art. An unexpected job offer from the literary magazine Matrubhumi, edited by the great Malayalam poet NV Krishna Warrier, provided Namboodiri with a stable income. MV Devan, his senior from Chennai who would go on to be a great painter, had also been working at Matrubhumi as a resident artist. In 1961, when Devan left for Chennai, young Namboodiri began to draw extensively for the publication. From his early days, Namboodiri had been given the freedom at Matrubhumi to draw on his own; time and the deadline were his only masters. His work for the magazine accompanied written texts by Kerala’s beloved authors and reached homes across the state and the region. It was a heady era for Malayalam literature: masters of realism like Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, subtle experimentalists like OV Vijayan, and, by the 1970s, ‘young Turks’ like MT Vasudevan Nair and M Mukundan had begun to make their mark. The Kerala society was undergoing a radical shift: its journey from the last vestiges of feudalism to the incipient chaos of a social market-based economy changed mores, entrenched poverty, brought new anxieties and, inevitably, led to great upheaval in art—via cinema, literature or painting. Not through any plan on his own, Namboodiri was involved in all three.

Most famously, his illustrations provided the common reader with a visual entryway into the text. People understood the heroes and the villains through Namboodiri’s depictions. He brought about a change in the visual aesthetics of the masses: suddenly, heroines weren’t coquettish maidens and heroes weren’t represented as paragons of the physical form. His women were amply breasted and had moles and warts; his men had double chins and sumptuous bellies. It would not be an exaggeration to say that, on occasion, many readers may have skipped the text and simply enjoyed Namboodiri’s ink strokes. Alongside his work for the two magazines, he frequently drew for other publications and literary works: line drawings of his observations from his travels became staple references wherever Malayalam was read. By this time he had also become a prolific political cartoonist for a Malayalam newspaper that was also called Matrubhumi. Namboodiri’s cartoon strip, called ‘Nannniammayum Lokavum’ (‘Nanni-amma and the world’), introduced a new generation to his informed skepticism of the claims of democratic politics. His stint at Matrubhumi also gave him enough time to explore other mediums of art. He began to paint canvases, sculpt in wood and take on art direction for films.

To many in Kerala, all it takes to confirm the artist behind the work is a raised eyebrow and a monosyllabic query: “Namboodiri?”. Half a century of work has lifted him to iconic status. To writers of op-eds and essays, he has become an adjective (“Namboodiri like”), a noun (“…is a Namboodiri”) and a putdown (“…thinks he is like Namboodiri”). By now, he has learnt to ignore his popularity. Instead, he continues to work without the anxiety created by other people’s expectations.

He has willfully sought stillness in the maelstrom of the art circuits. Shorn of philosophical pretense, he continues to mine his favourite inspiration: Kerala. He observes her—horrors and disfigurations included—with love. His lines have become more austere, his quest for the ‘bhava’ of a scene still animates him, his figurines have a sense of movement, his crowds concatenate and swell past the page, his silhouettes emerge out of an expanse of white or merge inconspicuously into a fevered landscape. Age, and the lack of overwhelming acclaim, has not disillusioned him. If the years have had any effect, they have led him to simplify, to strip away the details, to progressively shed the superfluous. Hair, that he once drew as flailing sea serpents or frenzied creepers, is now, simply, a bunch of wires clumped together. What matters now are the brooding, the romance, the promise of frenzy and the nostalgia for quietude. “The rasa is crucial. Whether it is dance or painting!” he said to us. Then with a mischievous smile, he added, “If there is no rasa, there is no rasam.”

Namboodiri has continued to work at a clipped pace: he was about to travel to Indonesia (“Bali or Mali, I keep forgetting”) and Malaysia to visit some new installations based on his drawings; he was scheduled to visit Hampi in Karnataka for the documentary shoot; he was looking forward to a new project for the under-construction Chennai International Airport; he had to deliver new drawings to a magazine; he had young students working on bronze and copper in his studio; and, yes, he had to anticipate celebrating his 87th birthday. (“They [his children and friends] keep insisting.”)

The world beyond Kerala and India has, of late, begun to discover his art. It resonates with them even though it is resolutely steeped in local contexts. Popular visual art in Kerala is overwhelmingly influenced by the aesthetics of the ‘kshetra-kala’ (the temple arts), the legacies of Raja Ravi Varma and cinematic posters. The state has few modern art museums and few people visit them. The possibilities for new work to enter into the popular consciousness are few, except via the sanctified gallery halls run either by the government or the elite. A surprisingly large number of new artistic expressions have emerged out of Kerala, but have had difficulty surviving in their native soil. Malayali artists and painters have settled in cities as distant as Mumbai or Delhi or Baroda, showing their works all around the world, yet, there continues to be a disjoint between their neo-expressionist responses to modernity and society in Kerala. Not only that, but there also exists a certain cognitive dissonance between Kerala and her creative children who explore modernity. Connoisseurs and buyers of modern art experience a different trajectory of aesthetic evolution than the large parts of middle class. This social divide between the aesthetic responses to art and views on how history ought to be represented continues to widen. Namboodiri is one of the few artists who seek to bridge this divide. One who understands the vocabulary of modern art (“We must work to make ourselves more aware of ideas, more contemporary.”) and yet also knows of life amid the temples, the elephants, of the road construction scams in the village. His work over the past 50 years has been among the most consequential efforts to whittle away the dominant temple paradigm that had roots in a pre-modern historic context. But like all artistic works that rupture a paradigm, the acculturation between his aesthetic vision and the sensibilities of his society has metamorphosed. This union, if you will, of the artist and his society had collected historical debris over the years and was enshrouded by the curse of familiarity. Over the past two decades, Namboodiri’s work has percolated back into the popular consciousness. It may have to do with “mechanical reproduction”—television, magazines, documentaries. Namboodiri is aware of the power of technology. But his approach to the craft has not changed. His ideas still flow from his fountain pen and onto pads of paper. (One wonders where the rough drafts of all his sketches are lying about?) I told him about using a Wacom tablet to draw, about the sorcery of Photoshop and how metallic frames and facades can be cut using computer programmes. He was curious to know more—who uses it, how fine can they slice, is it easy to manipulate? And, finally: “Does all this technology create art?”

“Maybe.”

“Yes, maybe it does.”

And then he smiled. He wasn’t very convinced.

Essentially, Namboodiri’s popularity has emerged from his willingness to share his art—often without any monetary compensation. That he rarely sells his canvases, but rather gives them away, makes him an anomaly in the hypercompetitive art world. In the sea of self-promoting porpoises, he is the blue whale that swims deep underneath the surface. He has no website, though a few friends recently created a Wikipedia page for him. The cultural grandees and bureaucrats find his unwillingness to speak the vocabulary of despair and modernist anxiety puzzling. It is easier to ignore him, they seem to have concluded. Perhaps there is a cost to his willful withdrawal from the usual games. He is yet to be honoured with the most basic of India’s civilian awards. It doesn’t help that he often relates in public, with impishness and relish, the anecdote about his friend VKN who, after receiving an award from the Central Sahitya Academy, folded the parchment and slid it up into his attic to collect dust and feed the termites. VKN may have been a fierce wit, but Namboodiri is no less so. He too has that subversive streak, but is gentle in manner. Perhaps that is why they both got along well. One wrote while the other drew the inanities of Kerala’s public life.

Despite having been neglected by the establishment, Namboodiri continues to be sought out by other artists. He serves as a visual interpreter to works by young writers and old friends, like MT Vasudevan Nair; a collaborator with the great Kathakali maestro Kalamandalam Gopi or the young Carnatic singer Sreevalsan J Menon; even a costume designer for young dancers of Mohini Attam.

Perhaps in an effort to understand the arc of his own life, he has taken to drawing and narrating his autobiography. Over the past 100 issues of the esteemed literary journal Bhashaposhini, Namboodiri has extensively sketched alongside his written memories. It serves as a fascinating account of a world much of which is now lost. Memory can be tricky, but he insists on striving for fidelity. In an interview with the author NP Vijayakrishnan, Namboodiri said, “The only thing I am stubborn about is that my words and writing are not laced with exaggerations…. The consequence may be that some of the writing may lack a ‘punch’.”

There is no sense of false humility in his writing. Few details about his family emerge. What preoccupies him are his observations about the material space he inhabits—the visual possibilities, the changing contours of India. His literary minded admirers call these sketches “Atmachitram”, the drawings of the soul or the drawing of oneself. He prefers them as just “rekha chitram”, simply line drawings. At an average of 10 drawings per issue, he has now drawn nearly 1,000 or more vignettes. Few aspects of life seem to have escaped him, few seem to disinterest him. This sort of old-fashioned creative stamina, to relentlessly create content without bombast, sans the paraphernalia of self-aggrandizement, is something his viewers and readers intuit. It takes time, but the collective wisdom of the people knows the wheat from the chaff. Here, they say, is an original. An artist.

Driving across Kerala reveals how the influence of Namboodiri reaches the most unexpected places. In villages, ramshackled gyms put up imitations of Namboodiri’s Bhima for Randaamoozham next to photographs of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Saree shops display on their signboards his sketches of women—their bodies tantalizingly draped. Beauty salons advertise arched eyebrows and puffed-up hair inspired from his old drawings. Young artists tout their wares: their versions of Namboodiri’s sketches for literary novels, autobiographies and canvases. This appropriation of Namboodiri by the aspirants in ‘new’ India is perhaps his greatest triumph—the transformation of his art into a public celebration. This manipulation of his art, as sociologist MN Srinivas puts it, facilitates the “Sanskritization” of popular aesthetics. It is, in many ways, no different than when undergraduate students wear T-shirts with Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ to bar brawls or Rodin’s ‘The Thinker’ finds itself on mugs used for beer pong.

The proliferation of Namboodiri’s work in the public domain has inevitably attracted (implicit) questions about his political affiliations; an ideological masthead to which his canvas may be strapped. In recent years, he has rarely commented in public on Kerala’s politics. Yet, it is not hard to discern his progressive instincts—his suspicion of all forms of authority, including that of the Communist parties. He was born at the cusp of a great historic tumult in the Namboodiri community. By his teens, social reformers like VT Bhattathiripad, Arya Pallom, Lalithambika Antharjanam, MR Bhattathiripad, Parvathy Nenminimangalam and, most famously, EMS Namboodiripad were household names in Kerala. These men and women had broken away from centuries of institutionalised repression of women and lower castes, shed liturgical orthodoxies, pushed for widow remarriages and education for girls, and demanded an end to polygamous arrangements with the Nairs of Kerala.

His literary minded admirers call these sketches “atmachitram”, the drawings of the soul or the drawing of the self. He prefers them as just “rekha chitram”, or simply line drawings.

In 1957, EMS led the first democratically elected Communist government in Kerala. Young Vasudevan Namboodiri watched members of his caste celebrate the ascent of one of their ‘own’ to the halls of power; and in an ironic twist, the EMS administration instituted land reforms which put anend to centuries old ‘theocratic feudalism’. It was in an era of overwhelming poverty across Kerala that Namboodiri came of age. The ideologies and philosophies that inform politics still interest him; but the grotesque political parlour games of today arouse a despondent laughter. Yet, for all its misshapenness, he does not believe that the past was better. Neither is there a utopia that he awaits. These days, he’s often asked to appear at inaugurations and birthday celebrations. This new mode of public engagement wears him out. The routine of his day is disrupted. But he is game for most of it. “When those who are friends and those whom I admire ask for me, I never say no.” There is no reason to disappoint them. All they want is to have him draw for them, sometimes in public. This ‘performance’ part of his art still unnerves him. “For one hundred onlookers, there are two hundred eyes staring. Somehow, I manage to do well.”

What happens to his canvases after the public performances? “Some the organisers take away, some I don’t know. Each one of them has its own fate.” His house bears little evidence of his own work. His favorite spot is the veranda: the precipice where the house ends and the world begins. This is where we had been sitting for more than five hours. We were on our way to another engagement, and had come to meet Namboodiri for 30 minutes, but the other plans were dashed. Nobody seemed to mind. Namboodiri was showing us the postcards VKN had sent to him, filled with irreverent repartee on the absurdities of modern India. We sat laughing about them. At the heart of Kerala’s hyper-political social life, there is a fondness for sacrilegious humour. Nobody is aboveboard. Nothing is sacred. Somebody, someday, should publish these postcards.

I left the veranda and wandered around the house. Immediately, I was enveloped by a deep and resounding silence, interrupted only by the nightly buzz of insects and the braying of automobiles in the distance. Namboodiri’s wife and family were away. Inside the house was a courtyard, almost half the size of a squash court. Through it, one could stare up at the star-speckled sky. During monsoons, rainwater must fall inside the house through the courtyard, and splash into the open kitchen.

The 18 pillars that frame the courtyard are from Karaikudi in Tamil Nadu, where the present generations of Chettiars have slowly begun to demolish their ancestral homes; their Athangudi tiles, hand-carved stone pillars and facades with stucco sculptures have made their way into the houses of connoisseurs across South India.

Unlike others who mourn the decrepitude of heritage buildings on account of human negligence and the inescapable workings of nature, Namboodiri seemed to feel an added dimension of loss—a melancholy as he would see a visual culture, a colour-filled aesthetic that took centuries to evolve, just wither away. Kerala, like Tamil Nadu, hasn’t been spared in its desolation. Manors of all kinds—the illam, manaa and the theravadu—which are often sites of great cultural and historic importance, have been systematically demolished. Later, distracted, Namboodiri pointed to his new and elegantly designed home, and almost wistfully said, “This is not really my illam”. The move away from the ancestral home, the repository of his early childhood memories, still matters to him.

Unlike many of our artists who have emerged out of the swamps of in-betweeness, and who willfully cultivate an exilic condition, Namboodiri has never had use for diasporic anxiety. And this rootedness has allowed him to discover a gamut of humanity in Kerala itself, as RK Narayan did in the fictional world of Malgudi, or William Faulkner did in Yoknapatawpha County. His lines reek of the grime and sweat of daily life. Without angst about authenticity, he finds subtleties in his subjects. His quest is not for verisimilitude, his technique is not marked by an aesthetic obstinacy, nor is his idea of belonging a cloying identification with a place. Unique to his own character is a willingness and patience to investigate the mores of Indians. It is not something that can be taught in art schools. To be able to laugh at their hypocrisies knowing very well that by doing so he might be laughing at himself. This self-awareness prevents him from self-indulgence. His works have become a canon unto themselves. Monuments in time that will outlive its creator, its admirers and detractors. Perhaps there can be no more of a reward for an artist, whether he agrees to be one or not.

—

A version of the essay was published in The Caravan, April 2012.